High-voltage power transmission frameworks featuring cutting-edge transformer technology, paired with laser visualization tools, highlight the pivotal role of efficient power conversion in modern energy networks. For transformer manufacturers, utilities, and industrial facility managers, understanding the dynamic nature of transformer efficiency is more than a technical exercise—it is a cornerstone of cost-effective, eco-friendly power system operation. Transformers, which operate relentlessly for 30–40 years on average, quietly consume energy even when powering minimal loads. Over their service life, seemingly negligible efficiency gaps translate into massive cumulative energy waste, inflated utility bills, and elevated carbon footprints. This is why transformer efficiency is not merely a performance specification, but a critical economic and environmental parameter that regulators, energy providers, and end-users scrutinize closely.

Unlike common misconceptions that transformer efficiency is a fixed value, it shifts continuously based on the load magnitude the unit carries. Grasping the relationship between load levels and efficiency requires a deep dive into the inherent energy losses within transformers, how these losses behave under varying operational conditions, and how to tailor transformer selection and usage to maximize efficiency. By dissecting the mechanics of core and winding losses, operators can unlock substantial savings, extend transformer lifespans, and align their power infrastructure with global energy efficiency mandates.

Contents

hide

What Is Transformer Efficiency and Why Is It a Critical Metric?

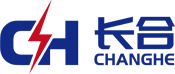

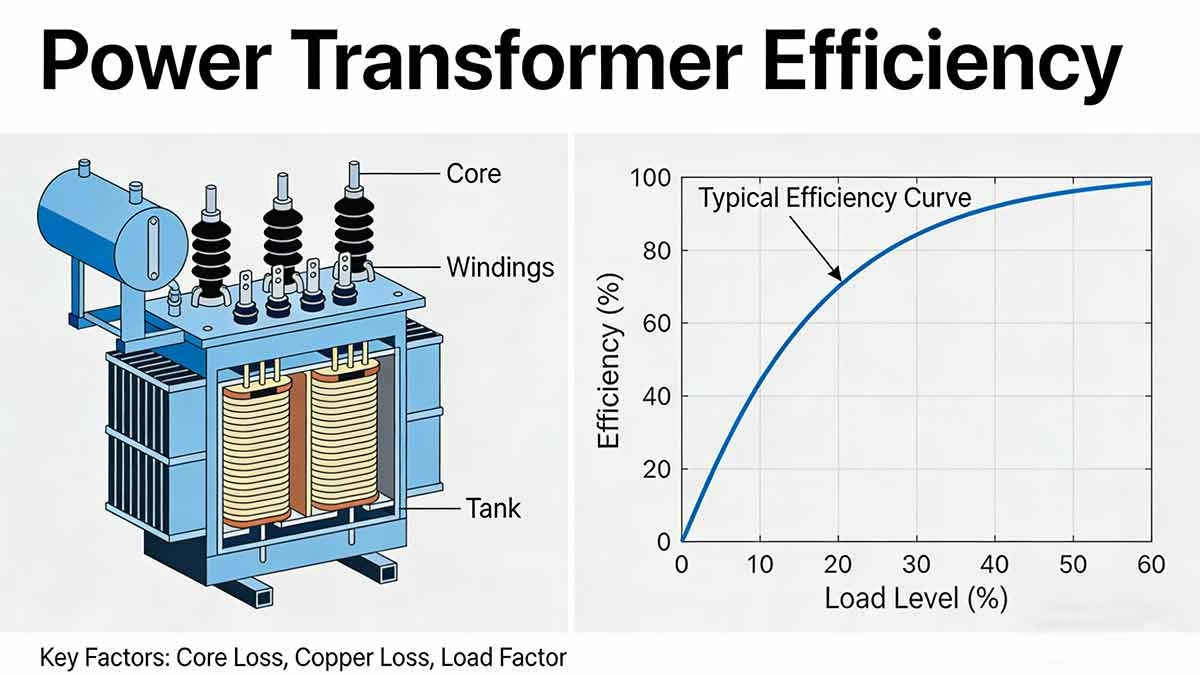

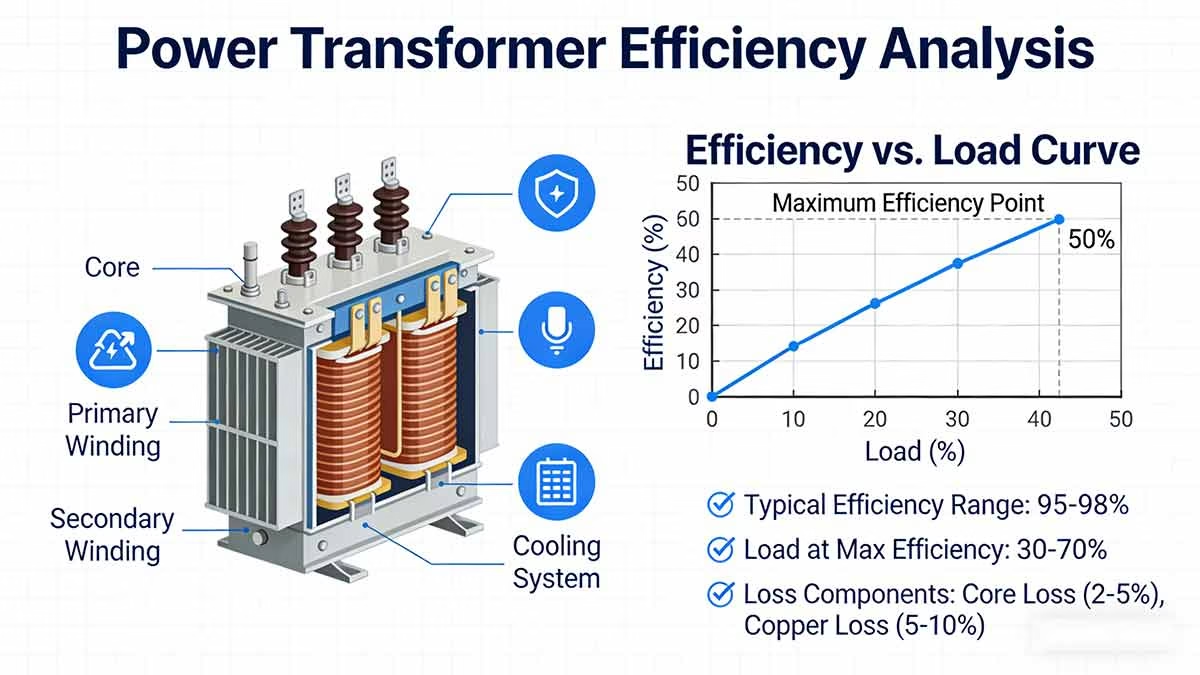

Transformer efficiency refers to the percentage of input electrical power that is successfully converted into usable output power, with the remaining portion dissipated as energy losses. Mathematically, this relationship is expressed as:

Efficiency (%) = (Output Power ÷ Input Power) × 100

The disparity between input and output power stems from unavoidable energy losses within the transformer. Unlike rotating electrical machines such as motors or generators, transformers have no moving components, meaning nearly all efficiency losses are rooted in electromagnetic and resistive phenomena rather than mechanical friction.

Two core efficiency concepts are indispensable for practical power system management: peak efficiency and all-day efficiency. Peak efficiency denotes the maximum efficiency a transformer achieves at a specific load point, while all-day efficiency—also called energy efficiency—reflects the unit’s performance over a full 24-hour load cycle. For distribution transformers, which supply power to residential neighborhoods, commercial districts, and small industrial zones with highly variable load demands, all-day efficiency holds greater significance than peak efficiency. This is because distribution transformers remain energized around the clock, even during off-peak hours when load levels plummet to 20–30% of rated capacity.

Transformers stand out as the most efficient electrical devices in modern power grids, with large power transformers boasting efficiency ratings exceeding 99%, and distribution transformers typically ranging from 97% to 99%. This exceptional efficiency stems from three key design and operational factors: the use of high-grade magnetic core materials that minimize magnetic energy waste, the absence of mechanical components that would introduce friction losses, and stable electromagnetic operating conditions that reduce energy dissipation from flux fluctuations.

The economic implications of transformer efficiency are profound. A mere 0.5% improvement in efficiency can translate to tens of thousands of dollars in energy savings over a transformer’s service life. Lower energy losses reduce cooling system requirements, cutting both capital and operational costs for cooling fans and oil pumps. Additionally, reduced heat generation slows insulation aging, extending the transformer’s lifespan and deferring costly replacement or refurbishment expenses. In many cases, the premium paid for high-efficiency transformers is recouped within 5–7 years through energy savings, making them a cost-effective long-term investment.

From an environmental perspective, transformer losses directly correlate with increased power generation and greenhouse gas emissions. Every kilowatt-hour of energy lost to transformer inefficiencies requires additional power to be generated, often from fossil fuel-fired plants. High-efficiency transformers reduce carbon dioxide emissions over their operational life, help utilities meet regulatory sustainability targets, and support global efforts to mitigate climate change. As a result, more than 80 countries have implemented mandatory minimum efficiency standards for transformers, classifying units into efficiency tiers and restricting the sale of low-efficiency models.

What Are the Key Loss Types That Undermine Transformer Efficiency?

Substation landscapes at dusk, featuring rows of transformers, circuit breakers, and overhead power lines, showcase the intricate infrastructure that powers modern societies. Despite their exceptional efficiency, transformers are not loss-free. Every unit converts a small fraction of input power into heat, audible noise, and stray electromagnetic fields. Over decades of operation, these incremental losses accumulate into significant energy costs, thermal stress on transformer components, and environmental impact. Understanding the full spectrum of transformer losses is essential for optimizing design, selecting the right transformer for specific applications, and minimizing lifecycle costs.

Transformer losses are defined as the portion of input power that fails to reach the load, instead being dissipated as heat due to magnetic, resistive, and auxiliary system effects. These losses are inherent to electromagnetic energy conversion, but advanced materials and engineering techniques can drastically reduce their magnitude. Core magnetization processes, conductor resistance, and leakage magnetic flux all contribute to energy dissipation during normal transformer operation—making losses an unavoidable, yet manageable, aspect of transformer performance.

Core Losses (No-Load Losses)

Core losses, also referred to as no-load losses, occur whenever a transformer is connected to a power source, regardless of whether it is supplying power to a load. These losses originate from the alternating magnetization of the transformer’s magnetic core, which is typically constructed from laminated silicon steel or amorphous metal alloys.

Core losses encompass two primary components: hysteresis losses and eddy current losses. Hysteresis losses arise from the repeated reversal of magnetic domains within the core material as the alternating current changes direction. Each time the magnetic field flips, energy is required to realign the domains, and this energy is dissipated as heat. Eddy current losses, by contrast, are caused by circulating electrical currents induced within the core itself by the alternating magnetic flux. These currents flow through the core material, generating heat via resistive dissipation.

The magnitude of core losses depends on three key factors: the applied voltage level, the frequency of the power supply, and the quality and thickness of the core material. Thinner core laminations, for example, reduce eddy current paths and lower eddy current losses by up to 40% compared to thicker laminations. Since core losses persist 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, for energized transformers, they are a primary concern for distribution transformers that operate at light loads for extended periods.

Winding Losses (Load Losses)

Winding losses, commonly known as load losses, are tied directly to the load current flowing through the transformer’s primary and secondary windings. These losses are driven by the electrical resistance of the winding conductors, which are typically made from copper or aluminum.

A defining characteristic of winding losses is their proportionality to the square of the load current—a relationship described by the Joule heating law (P = I²R). This means that doubling the load current quadruples the winding losses, while tripling the current increases losses ninefold as transformers carry heavier loads, winding temperatures rise, which further increases conductor resistance and amplifies losses—a positive feedback loop that can lead to overheating if not managed properly.

The size of winding losses is influenced by three variables: the conductivity of the conductor material (copper has 60% higher conductivity than aluminum), the cross-sectional area of the conductors (larger conductors reduce resistance), and the operating temperature of the windings. For high-efficiency transformers, manufacturers often use thicker copper conductors to minimize resistance and lower winding losses, even though this increases the unit’s initial cost.

Stray Load Losses

Stray load losses are a secondary but significant category of losses that stem from leakage magnetic flux—magnetic field lines that do not follow the intended path through the transformer core and instead spread into the surrounding tank walls, clamps, bolts, and structural components.

These losses include two main components: eddy currents induced in the transformer’s metal structural parts, and additional heating in the windings caused by non-uniform current distribution. In large power transformers, which handle megavolt-ampere (MVA) load levels, stray load losses can account for 10–15% of total load losses. This is why manufacturers use non-magnetic materials for transformer tank clamps and bolts in high-capacity units—to reduce stray flux interactions and lower associated losses.

Dielectric Losses

Dielectric losses occur within the transformer’s insulation system, which is responsible for separating the high-voltage windings from the low-voltage windings and the core. These losses are caused by the alternating electric field applied across insulating materials such as mineral oil, cellulose paper, epoxy resin, or solid cast resin.

The magnitude of dielectric losses depends on four key factors: the type of insulation material, the moisture content of the insulation, the degree of insulation aging, and the operating voltage and frequency. Fresh, dry insulation has minimal dielectric losses, but as insulation ages or absorbs moisture, its dielectric properties degrade, leading to higher losses. For this reason, dielectric losses are often used as an early warning indicator of insulation degradation during transformer maintenance inspections. A sudden spike in dielectric losses can signal moisture intrusion or insulation breakdown, allowing operators to take corrective action before a catastrophic failure occurs.

Mechanical and Acoustic Losses

Although transformers have no moving parts, they experience minor mechanical and acoustic losses related to magnetostriction—a phenomenon where the magnetic core expands and contracts slightly as the magnetic field alternates. This periodic expansion and contraction causes core vibrations, which propagate through the transformer structure and produce audible hum.

While these losses are small in terms of power—typically less than 1% of total losses—they are critical for noise control, especially in transformers installed in residential areas or urban environments with strict noise pollution regulations. Manufacturers reduce mechanical and acoustic losses by using tighter core clamping systems and damping materials to minimize vibration transmission.

Auxiliary Losses

Auxiliary losses are not directly related to the transformer’s electromagnetic operation, but rather to the support systems that keep the unit running safely. These losses include the power consumed by cooling fans, oil circulation pumps, temperature monitoring devices, and control systems.

In forced-air or forced-oil cooled transformers, auxiliary losses can become substantial during high-load operation. For example, a large power transformer with multiple cooling fans may consume 5–10 kW of power just to operate its cooling system during peak load conditions. This is why auxiliary losses are included in total efficiency calculations for modern transformers, as they can significantly impact the unit’s all-day efficiency.

The dominance of different loss types shifts dramatically across varying operating conditions, as summarized in the table below:

| Operating Condition | Dominant Loss Category | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|

| No load / Light load | Core losses | Efficiency drops sharply due to fixed losses and minimal output power |

| Medium load | Balanced core and winding losses | Efficiency peaks at the optimal load point |

| Heavy load | Winding and stray load losses | Efficiency declines due to exponential loss growth |

| Aging transformer | Dielectric and stray load losses | Losses rise as insulation degrades and flux leakage increases |

All transformer losses ultimately convert to heat, which is the primary driver of transformer aging. Excessive heat accelerates insulation degradation, reduces conductor conductivity, and shortens the transformer’s service life. Even a 10°C reduction in operating temperature can double the lifespan of transformer insulation, underscoring the critical link between loss reduction and asset longevity.

International standards such as the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60076 series and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) C57 standards define rigorous methods for measuring and classifying transformer losses. These standards set maximum allowable loss limits, establish efficiency tiers, and provide a consistent framework for comparing transformer performance across manufacturers. Compliance with these standards ensures that transformers meet both technical reliability requirements and regulatory efficiency mandates.

How Do No-Load Losses Impact Transformer Efficiency at Light Load Conditions?

Field maintenance scenes featuring technicians servicing pole-mounted distribution transformers under clear, sunny skies highlight the day-to-day operations that keep power grids running smoothly. In real-world power systems, transformers spend a significant portion of their operational life at light load or near no-load conditions—especially distribution transformers that supply power to residential areas with low nighttime demand or commercial facilities that operate only during daytime hours. Under these conditions, no-load losses become the primary factor driving efficiency performance, often overshadowing the impact of other loss types.

At light load levels, no-load losses exert a disproportionate influence on transformer efficiency because they remain essentially constant, regardless of how much power the unit delivers to the load. Meanwhile, the usable output power is minimal, meaning that a large percentage of the input power is wasted on core losses. This dynamic causes efficiency to drop sharply, even though the transformer may appear to be operating under low-stress conditions.

No-load losses, as previously outlined, consist of hysteresis and eddy current losses in the transformer core. These losses are determined by the applied voltage and system frequency, not the load current, so they remain stable from no-load to full-load conditions. High-grade core materials such as amorphous metal alloys can reduce no-load losses by 30–50% compared to traditional silicon steel cores, making them an ideal choice for transformers that operate at light loads for extended periods.

The mechanics of efficiency decline at light load can be explained using a simple example. Consider a 500 kVA distribution transformer with a no-load loss of 1.2 kW. At no-load (output power = 0 kW), the efficiency is 0%, because all input power is wasted on core losses. At 10% load (50 kVA output), the output power is approximately 48 kW (assuming a power factor of 0.96). The input power is 48 kW + 1.2 kW = 49.2 kW, resulting in an efficiency of (48 ÷ 49.2) × 100 = 97.56%. At 30% load (150 kVA output), the output power is ~144 kW, the input power is 144 kW + 1.2 kW = 145.2 kW, and the efficiency rises to 99.17%. This example illustrates how efficiency improves as load increases, driven by the growing ratio of output power to fixed no-load losses.

In distribution networks, the average load factor—the ratio of average load to rated load—often ranges from 20% to 40%. This means that distribution transformers operate at light load for most of their service life, making no-load losses the primary contributor to total energy waste. Over a one-year period, the energy lost to no-load losses in a typical distribution transformer can exceed the energy lost to winding losses, highlighting the importance of low no-load loss designs for distribution applications.

The economic consequences of high no-load losses at light load are substantial for utilities and end-users alike. Continuous energy waste translates to higher electricity bills, while excess heat generation increases cooling costs and accelerates insulation aging. For a utility company operating thousands of distribution transformers, reducing no-load losses by 1 kW per unit can result in annual energy savings of millions of kilowatt-hours.

From an environmental standpoint, no-load losses are a significant contributor to transformer lifecycle carbon emissions. Since these losses persist 24/7, they account for a large share of the total greenhouse gas emissions associated with transformer operation. This is why modern energy efficiency regulations, such as the EU’s Ecodesign Directive and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) transformer standards, place strict limits on no-load losses for distribution transformers.

Manufacturers employ several design strategies to minimize no-load losses and improve light-load efficiency:

- High-grade core materials: Amorphous metal cores have a disordered atomic structure that reduces hysteresis losses by up to 70% compared to silicon steel.

- Thin laminations: Core laminations as thin as 0.2 mm reduce eddy current paths, lowering eddy current losses.

- Optimized flux density: Designing cores for lower magnetic flux density reduces hysteresis losses, albeit at the cost of a slightly larger core size.

- Precision core assembly: Tight control over core stacking and clamping minimizes air gaps, which increase magnetic resistance and core losses.

Proper transformer sizing is another critical strategy for mitigating the impact of no-load losses at light load. Oversized transformers—units with rated capacity far exceeding the actual load demand—have larger cores and higher no-load losses, which leads to poor light-load efficiency. For example, a 100 kVA transformer serving a 30 kVA load will have lower no-load losses and higher efficiency than a 200 kVA transformer serving the same load. Correct sizing, based on detailed load profile analysis, is one of the most cost-effective ways to optimize transformer efficiency at light load.

No-load losses are most impactful in the following applications:

- Distribution transformers in residential and commercial grids

- Standby transformers for backup power systems

- Transformers in renewable energy installations, such as solar farms or wind turbines, with variable output

- Urban substations with low nighttime load factors

In these applications, selecting transformers with low no-load losses delivers significant long-term benefits, including lower energy costs, reduced carbon emissions, and extended transformer lifespans.

Why Do Load Losses Surge as Transformer Load Levels Rise?

Industrial substation installations featuring high-capacity power transformers demonstrate the critical role of these units in transmitting bulk power over long distances. As transformer load levels climb from medium to high, the factors influencing efficiency shift dramatically. While no-load losses dominate at light load, load losses—specifically winding and stray load losses—become the primary efficiency limiter at high load. The nonlinear growth of these losses with load current is a key reason why transformers must be carefully sized, cooled, and operated within their design limits to avoid efficiency degradation and premature failure.

Load losses increase exponentially with load levels because they are primarily driven by current-dependent effects, most notably resistive heating in the transformer windings. This nonlinear relationship—governed by the I²R law—means that even modest overloads can lead to a disproportionate surge in losses and temperature rise. For example, operating a transformer at 120% of its rated load increases winding losses by 44% (since 1.2² = 1.44), which can push the unit’s temperature beyond safe operating limits if the cooling system is not sized accordingly.

The I²R relationship is the foundational principle explaining winding loss growth. When load current flows through the transformer’s primary and secondary windings, it encounters electrical resistance, which converts electrical energy into heat. Since power loss is proportional to the square of the current, small increases in load can lead to large increases in losses. This dynamic is further exacerbated by temperature-dependent resistance: as windings heat up, their electrical resistance increases, leading to even higher losses—a self-reinforcing cycle that can cause thermal runaway if not controlled.

For instance, a transformer with a rated load current of 1,000 A and a winding resistance of 0.01 Ω has a winding loss of (1,000)² × 0.01 = 10,000 W (10 kW) at rated load. At 110% load (1,100 A), the loss jumps to (1,100)² × 0.01 = 12,100 W (12.1 kW)—a 21% increase in loss for a 10% increase in load. At 150% load (1,500 A), the loss skyrockets to 22,500 W (22.5 kW)—more than double the rated loss. This example underscores why sustained overloads are detrimental to transformer efficiency and longevity.

Stray load losses also escalate with load levels, as leakage magnetic flux increases in direct proportion to load current. The stronger leakage flux induces more eddy currents in the transformer’s structural components and causes more non-uniform current distribution in the windings, leading to additional heating. In large power transformers, stray load losses can increase by 50–100% when the load rises from rated capacity to 120% of rated capacity, making them a critical consideration for high-load operation.

Two additional electromagnetic effects—skin effect and proximity effect—amplify load losses at high current levels. The skin effect causes alternating current to concentrate near the surface of the conductor, reducing the effective cross-sectional area available for current flow and increasing resistance. The proximity effect occurs when magnetic fields from adjacent conductors induce eddy currents in neighboring windings, further increasing resistance and losses. Both effects become more pronounced at higher currents and frequencies, adding to the overall load loss burden.

The impact of load loss growth on the transformer efficiency curve is distinct. As load increases from light to medium levels, output power rises linearly, while load losses rise quadratically. Efficiency improves until the point where load losses equal no-load losses—the optimal efficiency point. Beyond this point, load losses grow faster than output power, causing efficiency to decline. This is why transformers are designed to operate most of the time near their optimal load point, rather than at maximum rated capacity.

Transformer manufacturers address the challenge of rising load losses through several design and engineering strategies:

- High-conductivity conductors: Using copper instead of aluminum reduces winding resistance and lowers I²R losses.

- Larger conductor cross-sections: Thicker conductors increase the current-carrying capacity and reduce resistance.

- Advanced cooling systems: Forced-air or forced-oil cooling systems dissipate excess heat, allowing transformers to carry higher loads without overheating.

- Non-magnetic structural components: Using stainless steel or aluminum for tank clamps and bolts minimizes stray load losses.

- Winding segmentation: Dividing windings into smaller segments reduces skin and proximity effects by limiting current concentration.

Sustained operation at high load levels can have severe consequences for transformer performance and lifespan. Elevated winding temperatures accelerate insulation aging, reducing the transformer’s service life by 50% for every 10°C increase in operating temperature beyond the rated limit. Excessive heat can also cause oil degradation in oil-filled transformers, leading to sludge formation and reduced cooling efficiency. In extreme cases, high-load operation can cause winding insulation to break down, resulting in short circuits and catastrophic transformer failure.

Effective load management is essential for controlling load losses and optimizing efficiency at high load levels. Utilities and industrial operators employ several load management strategies:

- Avoiding chronic overloads: Limiting transformer operation to 80–90% of rated capacity during peak hours reduces load losses and heat generation.

- Parallel transformer operation: Using multiple smaller transformers instead of a single large unit allows operators to switch units on and off based on load demand, improving efficiency at light load and reducing load losses at high load.

- Real-time load monitoring: Installing smart meters and monitoring systems allows operators to track load levels and adjust operations to stay within optimal efficiency ranges.

- Load profile matching: Selecting transformers designed for the specific load profile of the application—such as high-efficiency power transformers for constant high-load transmission lines—ensures optimal efficiency across operating conditions.

How to Optimize Transformer Efficiency Across Variable Load Profiles?

Optimizing transformer efficiency across the full spectrum of load conditions requires a holistic approach that combines careful transformer selection, intelligent load management, and proactive maintenance. For utilities and industrial facilities with variable load demands, this approach can unlock substantial energy savings, reduce operational costs, and extend transformer lifespans.

The first step in efficiency optimization is selecting the right transformer for the application. This requires a detailed analysis of the load profile—including average load, peak load, load factor, and load variability—to match the transformer’s efficiency characteristics to the actual operating conditions. For applications with low average load factors (20–40%), transformers with low no-load losses (such as amorphous core units) are the best choice. For applications with high, stable load factors (70–90%), transformers with low load losses (such as copper-wound units) are more suitable.

Proper transformer sizing is another critical optimization strategy. Oversized transformers have higher no-load losses and poor light-load efficiency, while undersized transformers are forced to operate at high load levels, leading to excessive load losses and overheating. The ideal transformer size is one that matches the peak load demand while maintaining an average load factor of 40–60%—the range where most transformers achieve their optimal efficiency.

Intelligent load management is essential for optimizing efficiency across variable load profiles. Parallel transformer operation, also known as transformer banking, is a highly effective strategy for applications with variable load demands. By using multiple smaller transformers, operators can switch units on and off based on load levels, ensuring that each operating transformer runs near its optimal efficiency point. For example, a facility with a 200 kVA peak load and a 50 kVA average load can use two 100 kVA transformers instead of a single 200 kVA unit. During peak hours, both transformers operate at 100% load, while during off-peak hours, one transformer is switched off, leaving the other operating at 50% load—near its optimal efficiency point.

Proactive maintenance is also a key component of efficiency optimization. Regular maintenance tasks such as oil analysis, core and winding inspections, and insulation testing can identify issues that increase losses—such as moisture intrusion, insulation degradation, or core clamping problems—before they lead to efficiency degradation. For example, replacing degraded insulation can reduce dielectric losses by 30–40%, while cleaning core surfaces can lower hysteresis losses by removing contaminants that disrupt magnetic flux flow.

Upgrading existing transformers to high-efficiency models is another effective optimization strategy for aging power grids. While the initial cost of high-efficiency transformers is higher than that of standard models, the long-term energy savings often justify the investment. Many utilities offer rebates and incentives for transformer upgrades, further reducing the payback period.

Finally, integrating transformers into smart grid systems can enhance efficiency optimization. Smart transformers—equipped with sensors, communication modules, and intelligent control systems—can adjust their operation in real-time based on load demand, grid voltage, and frequency. These units can also provide real-time efficiency data to grid operators, enabling proactive load management and efficiency optimization.

Conclusion

Transformer efficiency is a dynamic parameter that varies significantly with load levels, driven by the shifting dominance of core and load losses across operating conditions. At light load, core losses remain constant, leading to low efficiency, while at high load, load losses grow exponentially, causing efficiency to decline. The optimal efficiency point—where core losses equal load losses—typically occurs at 40–70% of rated load, depending on the transformer’s design and application.

Understanding the relationship between load levels and efficiency is essential for proper transformer selection, system design, and energy management. For utilities and industrial operators, this understanding can translate to substantial energy savings, reduced operational costs, and lower carbon emissions over the transformer’s service life. By selecting transformers matched to the load profile, implementing intelligent load management strategies, and performing proactive maintenance, operators can optimize efficiency across the full spectrum of operating conditions.

As global energy efficiency regulations become increasingly stringent, the importance of transformer efficiency will only continue to grow. High-efficiency transformers are no longer a luxury—they are a necessity for building sustainable, cost-effective power systems that meet the demands of the 21st century.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Transformer Efficiency

Q1: Why isn’t transformer efficiency constant across different load conditions?

Transformer efficiency varies with load because the two primary loss types—core losses and load losses—behave differently as load changes. Core losses are fixed, regardless of load, while load losses grow with the square of the load current. At light load, core losses dominate, leading to low efficiency. At medium load, the ratio of output power to total losses is maximized, resulting in peak efficiency. At high load, load losses surge, causing efficiency to decline. This dynamic means efficiency is never constant across operating conditions.

Q2: How do core losses impact transformer efficiency in real-world applications?

Core losses are a critical factor in efficiency for transformers that operate at light load for extended periods, such as distribution transformers in residential grids. Since core losses persist 24/7, they account for a large share of total energy waste over the transformer’s service life. Reducing core losses through advanced materials like amorphous metal can cut energy waste by 30–50%, leading to significant cost savings and emission reductions.

Q3: What causes load losses to increase so rapidly at high load levels?

Load losses grow exponentially with load because they are governed by the I²R law—power loss is proportional to the square of the load current. As load increases, current flow through the windings rises, leading to higher resistive heating. Additionally, temperature increases at high load raise winding resistance, further amplifying losses. Skin and proximity effects also contribute to loss growth by concentrating current and increasing effective resistance.

Q4: At what load point does a transformer achieve maximum efficiency?

A transformer reaches maximum efficiency when core losses equal load losses. This optimal point typically occurs at 40–70% of rated load, depending on the transformer’s design. Power transformers, which operate at high, stable loads, are often designed for peak efficiency at 60–70% of rated capacity. Distribution transformers, which operate at light loads, are optimized for peak efficiency at 40–50% of rated capacity.

Q5: Why is transformer efficiency low at both very light and very heavy loads?

At a very light load, core losses are fixed while output power is minimal, meaning a large percentage of input power is wasted, leading to low efficiency. At very heavy loads, load losses grow exponentially due to the I²R relationship, and the heat generated increases winding resistance, further reducing efficiency. The optimal efficiency range lies between these two extremes, where the ratio of output power to total losses is maximized.

Q6: How does load variation affect the total cost of transformer ownership?

Load variation has a significant impact on the total cost of ownership (TCO). Transformers operating far from their optimal efficiency point waste energy, increasing utility bills. Excessive heat generation at high load accelerates insulation aging, leading to higher maintenance and replacement costs. By matching the transformer’s efficiency characteristics to the load profile, operators can reduce TCO by 10–20% over the transformer’s service life.

Q7: Does transformer type influence efficiency behavior across load levels?

Yes, transformer design has a profound impact on efficiency behavior. Distribution transformers are optimized for low average loads, with low no-load losses to improve light-load efficiency. Power transformers are designed for high, stable loads, with low load losses to minimize efficiency degradation at high loads. Dry-type transformers typically have higher no-load losses than oil-filled units, while amorphous core transformers have 30–50% lower no-load losses than silicon steel core units.

Q8: What are the most effective ways to improve transformer efficiency under variable loads?

The most effective strategies for improving efficiency under variable loads include: selecting transformers with efficiency characteristics matched to the load profile, sizing transformers to maintain an average load factor of 40–60%, using parallel transformer operation to match unit count to load demand, implementing real-time load monitoring, and performing proactive maintenance to reduce losses from insulation degradation and core issues.