Electric transformers are the unsung workhorses of modern electrical systems—quietly adjusting voltage levels to enable efficient power transmission and safe use in homes, businesses, and industries worldwide. By leveraging electromagnetic induction to transfer energy between circuits, these stationary devices bridge the gap between high-voltage power plants and the low-voltage needs of everyday electronics.

Having spent years immersed in the power industry, I’ve witnessed firsthand how transformers shape reliable, efficient electrical grids. In this guide, we’ll explore the inner workings, key components, diverse types, and real-world applications of transformers—demystifying the technology that keeps our world electrified.

Contents

hide

Transformer Fundamentals: What They Are and Core Capabilities

Imagine trying to connect a smartphone directly to a power plant’s transmission lines—it would be catastrophic. Transformers are the critical intermediaries that make electricity usable, converting voltage levels to match specific needs while ensuring safety and efficiency.

An electric transformer is a stationary electrical device that transfers energy between two or more circuits through electromagnetic induction, with no moving parts. Its design prioritizes reliability and precision, making it a cornerstone of electrical infrastructure.

Key Definitions & Core Functions

At their core, transformers perform four essential roles in electrical systems:

- Voltage Transformation: The primary function—either increasing (stepping up) or decreasing (stepping down) voltage to optimize power flow.

- Current Regulation: As voltage changes, current adjusts inversely to maintain consistent power output (per the principle of power conservation).

- Impedance Matching: Aligning the impedance of connected circuits to maximize power transfer efficiency, critical for sensitive electronics.

- Circuit Isolation: Electrically separating circuits while still transferring energy, enhancing safety and reducing interference in delicate systems.

Function-Driven Transformer Classifications

Transformers are categorized by their primary purpose, each tailored to specific applications:

| Type | Core Function | Real-World Application |

|---|---|---|

| Step-Up | Increases voltage | Power plants feeding electricity to long-distance transmission lines |

| Step-Down | Decreases voltage | Substations delivering power to residential neighborhoods |

| Isolation | Separates circuits (no voltage change) | Medical equipment and sensitive electronic devices |

| Autotransformer | Fine-tunes voltage (small adjustments) | Voltage regulators for industrial machinery, motor starters |

Why Transformers Are Indispensable

Transformers are non-negotiable for modern electrical grids because they:

- Enable efficient long-distance power transmission (high voltage reduces energy loss via resistance).

- Make electricity safe for daily use (stepping down 100,000+ volts to 120/240 volts for homes).

- Protect equipment and people by isolating circuits and preventing electrical faults from spreading.

In my experience designing power systems for commercial and industrial clients, the right transformer selection can mean the difference between a reliable grid and costly downtime. Transformers don’t just “change voltage”—they enable the entire ecosystem of modern electrification.

Electromagnetic Induction: The Science Behind Transformer Operation

The magic of transformers lies in electromagnetic induction—a fundamental principle of physics discovered in 1831 by Michael Faraday. This breakthrough laid the groundwork for modern power distribution, allowing energy to be transferred without direct electrical contact.

Electromagnetic induction occurs when a changing magnetic field induces an electric current in a nearby conductor. For transformers, this principle enables energy transfer between coils, forming the basis of voltage transformation.

How Induction Powers Transformers

Transformers rely on a precise interplay of magnetic fields and conductive coils to operate:

- Primary Coil Activation: Alternating current (AC) flows through the primary coil, creating a continuously changing magnetic field around it.

- Magnetic Field Concentration: An iron core (or magnetic core) channels this changing field, minimizing energy loss and maximizing coupling between coils.

- Secondary Coil Induction: The fluctuating magnetic field cuts through the secondary coil, inducing an alternating voltage in the conductor.

- Voltage Transformation: The ratio of turns between the primary and secondary coils determines the output voltage (more turns = higher voltage, fewer turns = lower voltage).

The Transformer Equation: Precision in Action

The relationship between input and output voltage is defined by the transformer equation— a cornerstone of transformer design:

Vs / Vp = Ns / Np

Where:

- Vs = Secondary (output) voltage

- Vp = Primary (input) voltage

- Ns = Number of turns in the secondary coil

- Np = Number of turns in the primary coil

For example, a step-up transformer with 100 primary turns and 1,000 secondary turns will increase voltage tenfold (e.g., 20kV → 200kV).

Efficiency & Power Conservation

Ideal transformers operate at 100% efficiency, meaning the power input equals power output (Vp × Ip = Vs × Is, where Ip and Is are primary and secondary currents). While real-world transformers aren’t perfectly efficient—core losses (hysteresis, eddy currents) and copper losses (resistance in coils) occur—modern industrial transformers achieve efficiencies exceeding 99%.

In practice, this efficiency is critical: a 1% loss in a large power transformer can translate to millions of dollars in wasted energy annually. That’s why manufacturers invest heavily in optimizing core materials and coil designs to minimize losses.

Transformer Anatomy: Key Components and Their Roles

From the outside, transformers may look like simple metal enclosures—but their internal structure is engineered for precision and performance. Every component, from coils to cooling systems, plays a vital role in ensuring reliable voltage transformation.

The core of a transformer consists of three foundational parts: primary coil, secondary coil, and magnetic core. Additional components enhance efficiency, safety, and adaptability to different environments.

Foundational Components

Primary Coil

- Function: Receives input voltage and generates the initial magnetic field.

- Construction: Insulated copper (or aluminum) wire wound tightly around one leg of the magnetic core. The wire gauge and number of turns are calibrated to handle the input voltage and current.

- Critical Design Factor: Wire thickness must accommodate the input current to avoid overheating; more turns = higher voltage handling capacity.

Secondary Coil

- Function: Converts the magnetic field back into electrical energy, delivering the transformed output voltage.

- Construction: Similar to the primary coil but with a different number of turns (determined by the desired voltage ratio).

- Critical Design Factor: Turn count directly dictates voltage output—more turns for step-up, fewer for step-down applications.

Magnetic Core

- Function: Acts as a “magnetic highway,” concentrating and directing the magnetic field between coils to minimize energy loss.

- Material: Laminated silicon steel (or amorphous steel for high-efficiency models), which reduces eddy current losses (circulating currents that waste energy as heat).

- Types:

- Core-type: Coils wrapped around the outside of the core (common in power transformers).

- Shell-type: Coils enclosed within the core (used for low-voltage, high-current applications).

Supporting Components for Performance & Safety

Transformers rely on additional parts to operate efficiently and safely:

- Insulation: High-grade materials (e.g., paper, epoxy resin) prevent short circuits between coil turns and layers, and between the core and coils.

- Cooling Systems: Oil-filled transformers use mineral oil (or biodegradable alternatives) to dissipate heat; dry-type transformers rely on air cooling or forced ventilation.

- Tap Changers: Adjustable connectors that alter the number of active coil turns, allowing fine-tuning of voltage output to compensate for grid fluctuations.

- Bushings: Insulated terminals that safely route high-voltage connections into and out of the transformer enclosure.

- Protection Devices: Circuit breakers, fuses, and temperature sensors to prevent damage from overloads, short circuits, or overheating.

How Components Work in Harmony

Every part of a transformer is engineered to work in sync: the primary coil generates a magnetic field, the core channels it to the secondary coil, and supporting components ensure efficiency and safety. A well-designed transformer balances coil turn ratios, core size, insulation quality, and cooling capacity to meet specific voltage, current, and environmental requirements.

Types of Electric Transformers: Tailored to Every Application

Not all transformers are created equal—each type is designed to solve specific challenges in electrical systems, from long-distance power transmission to protecting sensitive electronics. Understanding the differences helps ensure the right transformer is used for the job.

Transformers are classified by function, design, and application, with each variant offering unique advantages. Below’s a breakdown of the most common types and their real-world uses.

Step-Up Transformers

- Purpose: Increase voltage for efficient long-distance transmission.

- Design: Secondary coil has more turns than the primary coil (e.g., 1:10 turn ratio for 20kV → 200kV).

- Key Application: Power plants—stepping up generator voltage (11kV–25kV) to transmission line levels (155kV–765kV) reduces energy loss over hundreds of miles.

- Why It Matters: Without step-up transformers, transmitting electricity across regions would be impractical due to excessive power loss in wires.

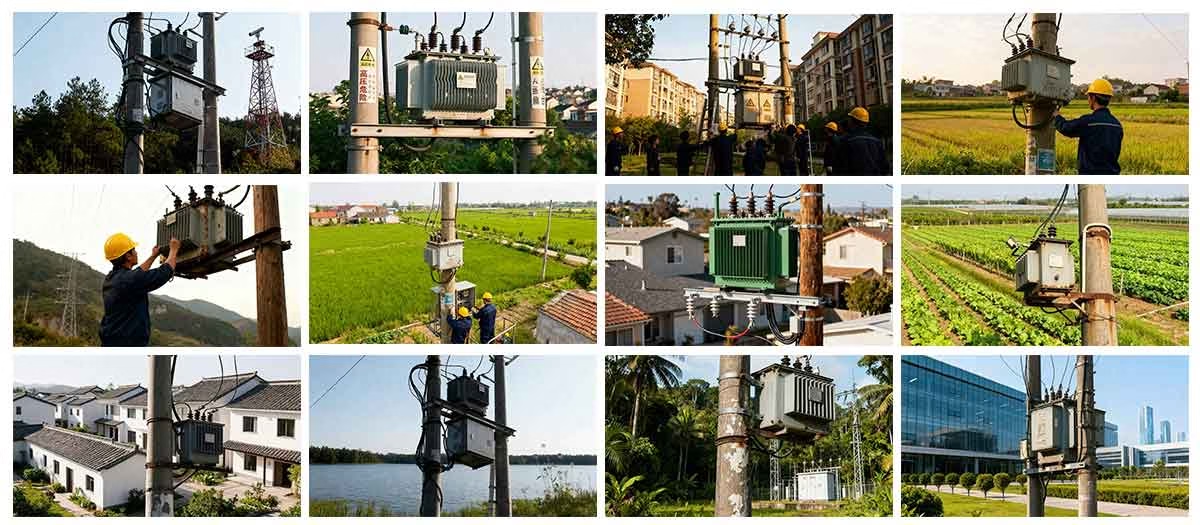

Step-Down Transformers

- Purpose: Decrease voltage to safe, usable levels for end-users.

- Design: Primary coil has more turns than the secondary coil (e.g., 10:1 turn ratio for 12kV → 120V).

- Key Applications:

- Substations: Reducing transmission voltages to distribution levels (4kV–33kV).

- Pole-mounted or pad-mounted units: Delivering 120/240V to homes and 208Y/127V to commercial buildings.

- Why It Matters: Makes electricity safe for appliances, electronics, and industrial machinery—preventing damage or electrocution.

Isolation Transformers

- Purpose: Electrically separate circuits while transferring power, no voltage change.

- Design: 1:1 turn ratio (equal primary and secondary turns) with reinforced insulation between coils.

- Key Applications: Medical equipment (prevents electric shock to patients), sensitive electronics (reduces interference), and industrial machinery (isolates control circuits from power circuits).

- Why It Matters: Eliminates ground loops, reduces electromagnetic interference (EMI), and enhances safety in high-risk environments.

Autotransformers

- Purpose: Make small voltage adjustments (±10–20%) more efficiently than traditional two-winding transformers.

- Design: Single winding with taps (no separate primary/secondary coils), reducing size and material use.

- Key Applications: Voltage regulators (compensating for grid fluctuations), motor starters (soft-starting large motors), and industrial processes requiring precise voltage control.

- Why It Matters: Higher efficiency (fewer copper losses) and lower cost than two-winding transformers for small voltage changes.

Instrument Transformers

- Purpose: Step down high voltage/current to measurable levels for monitoring and protection devices.

- Types:

- Current Transformers (CTs): Reduce high current (e.g., 1000A) to a standard 5A for meters and relays.

- Potential Transformers (PTs): Lower high voltage (e.g., 12kV) to a standard 120V for measurement.

- Key Application: Power system monitoring—enabling accurate metering, fault detection, and automatic shutdowns during emergencies.

- Why It Matters: Critical for grid reliability and safety, as they provide the data needed to manage and protect electrical systems.

Transformer Type Comparison

| Type | Primary Use | Voltage Change | Standout Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step-Up | Long-distance transmission | Increases (11kV→765kV) | Minimizes energy loss over large distances |

| Step-Down | End-user distribution | Decreases (12kV→120V) | Makes electricity safe for daily use |

| Isolation | Safety & interference reduction | None (1:1 ratio) | Protects sensitive equipment and people |

| Autotransformer | Voltage fine-tuning | Small (±10–20%) | Higher efficiency, compact design |

| Instrument | Monitoring & protection | Significant reduction | Precise measurement of high voltage/current |

Transformers in Action: Powering Transmission and Distribution

Electricity’s journey from power plant to your smartphone is a complex, transformer-driven process. At every stage—generation, transmission, distribution, and end use—transformers play a critical role in ensuring efficiency, safety, and reliability.

Let’s trace the path of electricity and explore how transformers enable each step of the journey.

Power Generation: The Starting Line

- Generator Output: Power plants (coal, natural gas, nuclear, renewable) produce electricity at 11kV–25kV—too low for long-distance transmission.

- Step-Up Transformer Role: Installed at the plant, these transformers boost voltage to 155kV–765kV. This reduces current (per V = IR), minimizing energy loss in transmission lines (losses are proportional to current squared).

- Real-World Impact: A 20kV generator connected to a 1:38 step-up transformer can feed 760kV into transmission lines, cutting energy loss by 99% compared to transmitting at 20kV.

Long-Distance Transmission: Crossing Regions

- High-Voltage Lines: Electricity travels hundreds of miles at 155kV–765kV. Transformers at substation hubs may adjust voltage slightly to match different transmission corridors.

- HVDC Transformers: For ultra-long distances (e.g., undersea cables), High-Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) systems use specialized transformers to convert AC to DC (and back to AC at the destination), reducing losses even further.

Sub-Transmission: Bridging to Distribution

- Voltage Reduction: Substations receive high-voltage electricity and use transformers to step it down to 33kV–155kV—ideal for distributing power to urban or industrial areas.

- Load Balancing: Transformers at this stage help balance power flow across the grid, ensuring no single line is overloaded.

Distribution: Delivering to Neighborhoods

- Primary Distribution: Electricity flows to local distribution substations at 4kV–33kV.

- Step-Down to End-User Levels:

- Pole-mounted transformers: Common in residential areas, stepping down to 120/240V (single-phase) for homes.

- Pad-mounted transformers: Used in commercial districts and industrial parks, delivering 208Y/127V (three-phase) for offices, retail, and small factories.

- Key Consideration: Transformers here are designed for durability and low maintenance, as they’re exposed to weather and require minimal downtime.

End-User Applications: Beyond the Grid

Transformers aren’t just for power distribution—they’re integral to everyday devices and industrial processes:

- Electronics: Small transformers in chargers (phones, laptops) and power supplies isolate circuits and adjust voltage.

- Industrial Machinery: Transformers power motors, welding equipment, and automated systems, providing stable voltage for precision operations.

- Renewable Energy: Solar inverters and wind turbines use transformers to convert DC power to AC and match grid voltage.

- Medical Equipment: Isolation transformers in MRI machines and operating room tools prevent electric shock and reduce interference.

Evolving Challenges & Innovations

As electrical grids adapt to renewable energy, electrification, and smart technology, transformers are evolving too:

- Smart Transformers: Equipped with sensors and communication tools to monitor performance, balance loads, and integrate with smart grids.

- Eco-Friendly Designs: Biodegradable insulating oils, dry-type transformers (no oil leakage risk), and recycled materials reduce environmental impact.

- Solid-State Transformers: Emerging technology that replaces traditional coils and cores with power electronics, enabling faster voltage adjustment and DC compatibility for EVs and solar.

Conclusion

Electric transformers are the backbone of modern electrification—enabling efficient power transmission, safe distribution, and reliable operation of everything from power grids to personal electronics. Their ability to adjust voltage, isolate circuits, and match impedance makes them indispensable in every corner of the electrical ecosystem.

From the massive step-up transformers at power plants to the tiny isolation transformers in medical devices, each type is engineered to solve specific challenges. As grids evolve to incorporate renewable energy, electric vehicles, and smart technology, transformers will continue to adapt—becoming more efficient, intelligent, and sustainable.

Understanding how transformers work, their key components, and the right type for each application is critical for anyone involved in electrical engineering, energy management, or infrastructure development. These remarkable devices may operate behind the scenes, but they’re the reason we can reliably power our homes, businesses, and the innovations of tomorrow.